A Collaboration with Left of Brown

‘In a world of possibility for us all, our personal visions help lay the groundwork for political action.’ – Audre Lorde

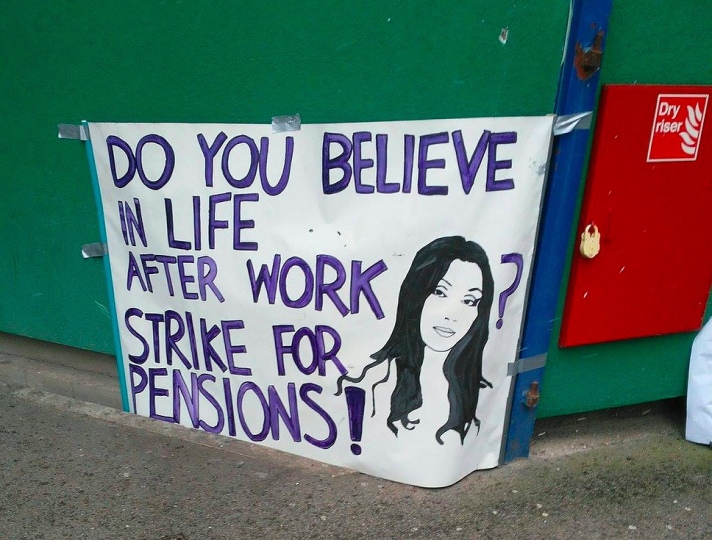

The current industrial pensions dispute taking place in UK higher education has exposed a serious rift in the sector, through which has broken the pent-up frustration and anger of staff and students alike over changes made in the past decade towards the marketized model of higher education. In this piece, we unpack and critique the present conditions which should be reflected in the emergent demands for a post-strike landscape, and put forward our suggestions.

While the union-led rolling strike and concomitant campaign against pension reforms are laudable in their mobilisation of thousands of staff, supported by student activists from across 68 universities, to enact unprecedented industrial action, we argue that they still fall short of their potential to address the wider problems within the sector. Some of these problems, such as the reproduction of intersecting white supremacy, gender bias and class oppression, are historical, normative, and generally unacknowledged. Others, such as the neoliberal ideological framework that enables and encourages the unbridled marketization of all sectors, are given lip service but have not been meaningfully addressed in the ongoing discussion around protecting pensions.

We note that protecting pensions is in itself a neoliberal demand. Neoliberalism reduces society to a conglomerate of agentic individuals competing against each other for scarce resources. It promotes the individual as sacred, and as such, an attack on the individual condition, like the future value of personal pension pots, gives cause for legitimate action. To illustrate, a key tool used to galvanise support for the strike was a spreadsheet circulated in which you could model your future expected pension payouts before and after the proposed reforms, in order to see how much you could be expected to personally lose. Pensions here became signified by a dispute over individual losses, rather than a structural impediment to the sector or assault on a public good. We take issue with this because of the existence of myriad structural conditions that merit collective resistance, and have yet to be addressed by the union or any other representative body.

The present pensions dispute is the result of a historical strategy led by successive governments that have changed the legal framework within which universities operate. The strategy was initiated as a partial marketization (monetizing knowledge through the REF and later commodifying learning via the TEF) to a more explicit assault on gold standard pensions that were the defining marker of public sector workers’ wage structure. According to Mike Otsuka, who has been writing extensively about the dispute, any deficit that may exist is traceable to a ‘pensions contribution holiday’ by employers from 1997-2009.

A marketized education system that has prioritised profit and growth over all else is unjust in many ways: it relies on the casualisation of labour and the precarity of employees, it follows the US model to charge outrageous student fees that produce debilitating debt, and allows the exorbitant remuneration of senior management in universities and USS, the pensions body (482% more in 2017 than 2008). The tools for structuring the HE market include various accreditation and ranking mechanisms such as the REF, TEF and the upcoming KEF (Knowledge Exchange Framework), which are widely acknowledged to be gamified and thus useless as measures of quality or legitimacy.

In the current institutional environment, it is undeniable that structural inequality amongst both staff and students is reproduced and in many cases exacerbated. However, national policy is way behind local initiatives that address intersectional inequality. University management is still overwhelmingly made of white males from the middle and elite classes, while women and people of colour, women of colour in particular, are confined to the lower ranks. To date, in the UK we have not had a single black principal or vice chancellor. According to Black British Academics, of 19,630 professors in the UK, 30 are black women – not even a quarter of one percent (0.15%). These kinds of blatant racial inequalities are commented on in news and media outlets, however, material interventions (such as affirmative action) have not been regarded as a viable approach by British labour jurisdiction. Instead, black mentoring and/or black networking are offered as voluntary initiatives that universities may wish to experiment with. To date, there is no evidence to suggest these initiatives are making any progressive changes to the working conditions of people of colour.

Regarding students, attainment gaps for students of colour and/or working class students are often reframed as issues of aspiration and lack of social capital. This is levelled by the right as well as the left of the political spectrum. Again, political discourse – and policy – reductively attributes a structural issue to the level of the individual, who is now easily blamed for their own supposed deficiencies.

Meanwhile, mechanisms such as the Athena Swan and Race Equality Charters enable the claim that inequality is being sufficiently ‘managed’ so that it no longer poses an issue, which furthers the illusion of a post-race/post-feminist society. Hitting these charter marks is now tied to application for future research funding; thus, the incentive for the mark is itself marketised rather than being motivated by a genuine aim to reduce inequality at that institution. Institutions which undergo these audit exercises can thus cite their participation as ‘evidence’ that a true market solves the problems of social and structural inequality. This fits squarely with the neoliberal belief that the invisible hand of the market works to adjust any disparity within systems.

If it were not already crystal clear it is this model that has been thrust upon us and that is being used to justify the attack on pensions, one need look only at the former asset-fund and corporate mining managers who make up the USS board of trustees to ascertain the modus operandi at work. Perhaps the tendency towards unethical behaviour in their former industries explains the incoherent evaluation of the health of the pensions fund that has been challenged by numerous experts in recent days. Claiming that the fund is in debt when it is not reduces liabilities and assists in the future borrowing which is expected to be the means by which to build shiny new buildings and attract more fee-paying international students.

While the proposals UCU has tabled at Tuesday’s ACAS talks (which were surprisingly brought forward from Wednesday after UUK was directly engaged via Twitter on Monday night) are sensible, there is a general lack of organising to form demands or even a position statement that goes beyond protecting pensions to firmly place the pension fight in the broader context of neoliberalism.

Pensions law specialist Ewan McGaughey takes a useful corporate governance perspective that moves us closer to imagining what a post-strike list of demands might look like, which we have built upon in some of our demands below. However, a significant limitation of this work is its implicit assumption that equitable governance is even possible within the existing framework. Drawing upon the critique offered by Audre Lorde, we are doubtful that the master’s tools can be used to dismantle the master’s house.

Visionary demands that explicitly critique the status quo drive community organising and political movements, and offer a focal point for negotiations as well as a rallying cry for those who support the position of those who are taking action. While the academic evaluations of the health of the fund have doubtlessly uncovered the surreptitious games being played with the sector’s future, we have yet to coalesce on a set of demands that address what we, who risk our reputations, job security (if there is any to be had), financial and mental health by striking and organising others to support the strike, would like to see going forward.

The ability to envisage a better future is integral to any social justice or liberation movement. It is the clarity of this vision that inspires people in their hundreds and their thousands to resist systemic oppression and to create lasting change. To that end, we offer below an initial list of demands suited to the current discussion of debt and value that we believe have the potential to radically alter the direction of travel of our sector. We call for a future that is less profit-driven and more focused on values aligned with institutions of higher education: equity, critical thinking, progress and social transformation, as opposed to simple reproduction.

- Accept and implement UCU proposal. The UCU proposal put forward at ACAS talks on Tuesday 6 March, including the reversal of the J23 changes to the September risk valuation, is accepted and implemented unconditionally.

- Disband UUK. Once the J23 changes are reversed, UUK is disbanded based on a vote of no confidence from their member institutions. Current requests to make UUK accountable to public scrutiny via Freedom of Information requests is a misplaced demand. This dispute has unequivocally demonstrated that UUK membership and voting is skewed towards the interests of elitist university managers and that representatives have no amount of accountability to or responsibility towards university workers. Instead we ask for a Workers’ Council to be instituted that is composed of trade unions, non-union workers and elected representatives from every paygrade.

- Accountability reform. The way universities, related bodies such as USS, and their leadership are held accountable must be completely reevaluated. Some suggestions to this end include: Each governing body should have a staff and student-elected majority.USS board members with potentially conflicting professional backgrounds should stand down, and the board should be comprised of a majority of staff members through direct election. VCs should not sit on committees that determine their own compensation.

- Fees must fall. We do not mean a reduction, we mean an eradication of student fees altogether. Education should be a central part of governmental budgets, funded by taxes. If, across the sector, universities are looking to make savings, VCs should turn their attention to pay ratios and making compensation across an institution more fair. If they work together to do this collectively, there is little risk of any single institution being unable to offer a ‘competitive’ compensation package to their most senior management.

- Revalue labour. The way labour at different levels of seniority is valued must be reimagined. Currently, outward-facing labour that promotes institutional reputation (i.e. high-ranking publications) is overvalued, while inward-facing, feminised and pastoral labour (i.e. teaching, administrative work) is undervalued. Yet it is this inward-facing labour upon which the university system runs, and it should be accounted for and valued accordingly.

- Address overrepresentation and underrepresentation. We distinguish this from diversity initiatives that use a positivist logic to make a claim of equality based on numbers of black, brown, gendered bodies at boards, panels, professoriate, etc. Instead, attention to over- and underrepresentation would mean addressing institutional inequities, such as the blatant inequalities between groups (UG students, PG students, PhDs, paygrade 1 versus paygrade 8 and beyond) and the numerous ways in which extant hiring promotion, reporting and disciplinary policies have (un)intended consequences of reproducing such differences.

- Dismantle white supremacy. Decentering white knowledge and scholarship is necessary for any meaningful reform of the sector. All managerial staff, but particularly white managers, should be trained to acknowledge and counter the subtle and overt racial discrimination that hinder the progress of people of colour within our institutions. While we acknowledge that the work intended by the Athena Swan and Race Equality Charter is needed, we believe that their aims should be written into the charters of all higher education institutions, which should actively encourage the reporting of discrimination and take concrete, measurable steps to address and rectify the issues identified. As Shirley Ann Tate asks, what if tackling racism became part of university performance indicators? That, she states, would be a revolution, because accountability to these indicators would require White Supremacy to acknowledge its own entitlement to the world it has created.