We begin this critique by invoking our foremothers: Audre Lorde, bell hooks, June Jordan, Angela Davis, Maya Angelou, Frida Kahlo, Yayoi Kusama, Jayaben Desai, Hortense Spillers, Gloria Anzaldua, Grace Lee Boggs, Gabriela Silang, and our grandmothers. We recognise and consciously continue their tradition of resisting colonising forces and speaking truth to power from the margins, and doing so, as they did, from a perspective of fullness and abundance rather than scarcity and lack. Their work laid the foundation for the radical intersectional politics that informs the powerful and formidable anti-oppression activist movements of our day, and shapes our enquiries and analysis here. In this vein, we wish to pose a question that, while painful in its vulnerability, is necessary in order to preserve the revolutionary aims at the heart of the decolonising movement, at a time when its radical politics are both under attack and gaining legitimacy: Is Decolonising the new black?

Within UK Higher Education, the call to decolonise, alongside other agendas that seek to address inequalities (e.g. Athena Swan and the Race Equality Charter Mark), is becoming a familiar demand heard by institutional actors.While Charter Marks serve Universities as mechanisms for gaining access to funding, we interrogate the acceptability of decolonising rhetoric as a sign that is it becoming co-opted by capital. Decolonising has entered consumers’ imaginations, and with it, a new kind of consumer has emerged: one that is politically astute and critical of Whiteness, but also firmly entrenched in conservative market forces that reproduce value through competitive means. In parallel, the ever increasingly marketised realm of British Academia is discovering (many would say in painful ways) that it is no different to consumer markets.

Whereas newer ranking systems such as the Teaching Excellence Framework have recently commoditized learning, the Research Excellence Framework has been creating competitive markets in academia for over a decade. The now acceptable notion of REFability points to the normalised attribution of financial value to knowledge, and its subsequent outcomes: job security, opportunities for promotion and mobility to other institutions. As a result, the motivation of publishers and authors has become mediated by the production of market value while the ancient University sector’s elitist, male, white, straight networks of power are reproduced. In this configuration, the possibility for political action through academic work has been muzzled; in a sector where one is no longer asked to publish or perish, but to publish in 4* academic journals or perish, other kinds of knowledge work recede due to their lack of marketable value (niche research is not the same as unmarketable research).

The financial and White structures that permeate British academic publishing should make us suspicious. Whiteness pervades and structures the socio-political context within which Universities operate and does so by articulating, promoting and sustaining practices that privilege neoliberal dynamics of exclusion and inclusion. In this respect, we should be especially vigilant when a journal title, academic conference or publisher associates a paper, sub-stream or book with the words ‘Decolonizing’ or ‘Black’ in their title with delivering some kind of value-added. This is not only concerning because of the mainstreaming and normalisation of oppression it suggests, but also because we are aware of how hard it is to do the work whilst fighting forces that continually pull towards assimilation into White capitalist structures of power, privilege and patronage. Here, we must state that we are not against decolonising work being embraced and used to overturn structures of power, nor are we against decolonising academics being valued and promoted. We are, however, critical of the accelerated circulation and consumption of decolonising within an archaic and elitist institution.

In asking whether decolonising is the new black, we mean: is decolonising becoming familiar to power structures in ways that its consumption, circulation and reproduction in the academy is diluting its radical politics? We question whether the rapid uptake of decolonising as the new buzzword of critique has become a new form of academic production that adds value to one’s reputation as a critical scholar while also opening a pathway to profit through making the histories, bodies, and experiences of Black people and people of colour consumable and marketable, transforming them into a viable subject for the entrepreneurial academic agenda. We identify a new form of appropriation, where it seems that decolonising is becoming factionalised along a political spectrum so that only parts of it are easily absorbed by Universities (and the people who govern them). This in turn supports the legitimation of HEIs as inclusive spaces without demanding that they engage in the painful process of self-accountability.

We welcome critique that leads to talking openly about and taking action against racism, imperialist ideologies, and colonial violence. However, when this critique is primarily rhetorical, and the accounts and histories of Blackness and its systematic structural oppression are denied presence and scrutiny in institutional narratives, as well as in everyday engagements between White management and academics and students of colour; then the critique is false, and as such must be called out and challenged.

We recognise false critiques all around us, which seem to emerge in the form of new practices and strategies of appropriation. These practices and strategies see the jubilant uplift of the privileged in taking elements of the Other away from the Other, re-configuring them in ways that no longer allow the Other to experience them as benefits, whilst simultaneously creating a branded image of ‘the oppressed’ that erases the possibilities for a resistant subjectivity. This process is one of recolonising in classical capitalist colonial form: Othering and claiming that which is the Other, seeking to assimilate it, exploiting and profiting from it all the while.

In other ways, this configuration materialises in the consumption of Blackness that simultaneously silences critiques of Whiteness. For example, we notice how when writing about people, dynamics and experiences in/of the Global South, White decolonial scholars have failed to reflect on their own privilege in and power over knowledge production. Whiteness thus remains the transparent structure that needs no naming, and with which critical engagement is impossible. When these issues are raised and addressed, whether in critical firsthand accounts of marginality, isolation and racist oppression or theorised in rigorous scholarly ways, they are often responded to with either hand-wringing and pearl-clutching by well-meaning White folks, or anger, aggression and victim-blaming by others. In this way, White fragility and anger are used as material strategies to diffuse responsibility in the articulation and perpetuation of dominant structures of oppression (i.e. if I didn’t care, this wouldn’t affect me so deeply). As a consequence, oppressive practices are rendered as isolated, individualised incidents, not taken for the structural issues manifesting in everyday occurrences and microaggressions that they are.

Given the political nature of academic production, we must also ask: who is doing this work, and for what reasons? As we noted, a number of White scholars are using decolonizing frameworks in their work without interrogating their own Whiteness/White-passing and their complicity in upholding White structures. In tandem, we note the consistency of this type of superficial engagement, and the surprising rate at which decolonizing work is being produced and circulated. The increasing use of the term alongside a lack of self-accountability potentially undermines the more radical politics of doing the work, in which the worker makes themselves vulnerable in situations where they encounter resistance. This is inherent to the experiences of those who engage in practices to dismantle power structures, but it is not evident in the way White scholars produce great value from adopting the term.

Further, it appears that academics with little evidence of anti-racist politics in previous scholarship and practice are emerging as leaders in these debates. This move should not only be questioned in terms of how it is impacting their positionality in their own institutions and amongst ‘critical’ scholarship communities, but also more fundamentally, in terms of the effects they seek (or do not seek) to bring about through their work. If the work they circulate is producing value for them in ways that multiply their privilege in the system, then it cannot be so easily claimed that their work is overturning the power structures within which it is being produced. Decolonising is radical because it identifies the current structures as inherently violent towards people of colour. Producing value in this system therefore strengthens it rather than dismantles it.

However, these discussions should not be seen as emerging exclusively from the academic domain. This work is facilitated by the present historical context, where there is a global anti-migrant and anti-refugee consensus, a re-emergence of fascism in Europe and the Anglo-American empire, and the overall systematic dumbing down of Western public discourse and popular education. A key feature of the current landscape is a lack of inclusive histories stacked up against the dismantling of democratic political processes in the Global South and the Global North, which has led to citizens being denied structural routes to influence decision-making, hardening their political positions and encouraging polarisation. These developments are not entirely new and have deep historical roots in colonialism and Cold War politics, but are certainly framed as such in the gestured surprise and confusion White Europe and Global North media outlets proclaim. This element of surprise correlates with how decolonising is being framed as a ‘novel’ or ‘new’ critique in academic circles so that it can be attributed some intellectual value (new ideas always get the most ticks and clicks!).

Nevertheless, despite the danger of superficial engagement with decoloniality multiplying, the need, importance and urgency of collective political work that democratises structures and creates inclusive platforms cannot be understated. In that respect, we recognise that opportunities are being created, spaces are being claimed and moments are being seized by different actors, where we see a breach opening up in the power structures of Whiteness, which is being enacted in ways that are politically radical and ethically nuanced. The fresh, radical and militant voices of Black and Brown young people worldwide continuing the unfinished antiracist and decolonising work of the 1960-70s have brought about this historical moment. Global youth of colour are challenging long-standing white supremacist institutions to grapple with their historical legacies of active participation and complicity in oppression. In the UK, student movements like #whyismycurriculumwhite, #whyisntmyprofessorblack and #rhodesmustfall have injected a vitality to Black liberation politics that has not been witnessed in decades in British Universities. Doing decolonising work in this context is powerful and brings a real possibility of becoming collective and transformative.

Decolonising is an incisive methodology countering the hard-right’s myopia, individualization, and competitive obsession. Decolonising work sets out to destabilise epistemic understandings, building consensus among the marginalized about a critical understanding of the White capitalist structures that continually de-value them. As such, its aims are always collective, collaborative and anti-competitive. Thus, the decolonising academic cannot seek to gain legitimacy in existing violent structures; doing so would only serve to reproduce these structures and deliver individual benefits. We argue that rather than measure and value the success of decolonising work through normative means e.g. number of publications, grant money accrued, and conferences attended, academics should measure the effectiveness of the work in its own terms, through serious engagement with the following:

-

Engaging with Whiteness with a sense of responsibility and self-accountability while acknowledging that for centuries people of colour have been denied their role in producing and shaping intellectual ideas and knowledge, even about themselves. One way is reading and citing what people of colour have written, and engaging with their ideas from a perspective that recognises the role of Whiteness in their struggles as well as the role of White complicity in reproducing oppressive structures. Another way is to engage critically with the global reach of Whiteness, making it central to discussions of pedagogy, anti-racism and decolonizing.

-

Re-narrating institutional histories so that narratives of racism and imperialism are not forgotten and are instead used in ongoing work that looks to reform universities, in ways that significantly make them anti-racist, anti-imperialist spaces. It is important to go beyond symbolic efforts that increase the brand value of universities (e.g. celebrating Black History Month) and engage with activities and practices that make universities vulnerable to external and internal critique.

-

Developing, applying and regularly reviewing organizing principles as a way of translating anti-racist and decolonizing ethics into applied and measurable methodologies. For this, it is central to actively work with students and staff of colour to seek to de-centre Whiteness in the curriculum, in classroom dynamics, in supervision relations, in staff promotion policies, in any disciplinary or grievance procedures, in mentoring and support relations, in knowledge production practices, and in administrative practices.

-

Working against intersectional racist structures so young people of colour can step into positions of power. This means addressing elitist, racist and sexist institutional structures and cultures, challenging and training those in power instead of demanding change from the most marginalised, and working to roll back the neoliberal university practices that result in the marketization of knowledge, because of which students of colour and poor students suffer, Black students in particular. Understanding and addressing these racial and class-based disparities is essential to decolonial work.

-

Organising within their own institutions to challenge racist practices and processes, including stepping back and giving up privileges, earned or unearned, as well as not continuing to hurt, violate or reduce the participation of people of colour in institutional spaces and processes (e.g. through admissions policies, IELTS policies, funding support, visa restrictions, and closing the attainment gap). The effectiveness of this organising relies on the involvement and leadership of students and staff of colour, whose voices and perspectives are central to understanding the impact of these processes.

-

Making oneself vulnerable in the act of political struggle with White capitalist patriarchy. Decolonising ethics involve a consistent de-centering of the self as well as encountering Whiteness in structures, arrangements and relationships, where personal desire, intentions and underlying assumptions should be brought under sustained scrutiny. This does not equate to using reflexivity as a way of legitimising what one is involved in and how one thinks about it. Decolonising work is a form of agitation; it is dangerous and powerful. If you are not putting your intentions under scrutiny, on your own and by those deemed Other, then you are not doing the work. If you are not upsetting Whiteness by doing the work, you are not doing the work.

-

Embracing solidarity as a radical act of self-effacement, where the Other determines the strength and quality of a relation. Respecting the autonomy of the Other is fundamental to wrestling with power dynamics that we co-construct when doing research that seeks to produce knowledge about the Other.

We believe that it is by focusing instead on these and similar priorities that genuine decolonising work is done. Anything less is simply recolonising.

This piece is a collaboration among Sisters of Resistance, Left of Brown, and Jenny Rodriguez.

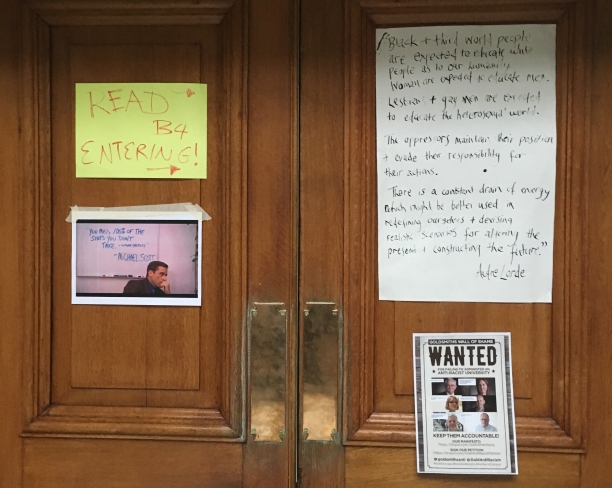

It is the 43rd night that undergraduate students of colour, led predominantly by Black, brown and Muslim women and queer folx and supported by white allies, have been in occupation at Deptford Town Hall, the face of Goldsmith’s University Campus in New Cross, South East London. The students are campaigning against the numerous manifestations of institutional racism they have encountered, many of them in their first year of university life. Considering the outstanding community organising undergirding the occupation, it may be surprising that most of the students were not previously involved in activism of any kind. Yet, in this final portion of the academic year, they have powerfully articulated and mobilised around a common cause and put their bodies and livelihoods on the line to attain the outcomes they seek, and in so doing have created the longest-standing student occupation in the history of Goldsmith’s University.

It is the 43rd night that undergraduate students of colour, led predominantly by Black, brown and Muslim women and queer folx and supported by white allies, have been in occupation at Deptford Town Hall, the face of Goldsmith’s University Campus in New Cross, South East London. The students are campaigning against the numerous manifestations of institutional racism they have encountered, many of them in their first year of university life. Considering the outstanding community organising undergirding the occupation, it may be surprising that most of the students were not previously involved in activism of any kind. Yet, in this final portion of the academic year, they have powerfully articulated and mobilised around a common cause and put their bodies and livelihoods on the line to attain the outcomes they seek, and in so doing have created the longest-standing student occupation in the history of Goldsmith’s University.

We have a big problem –

We have a big problem –